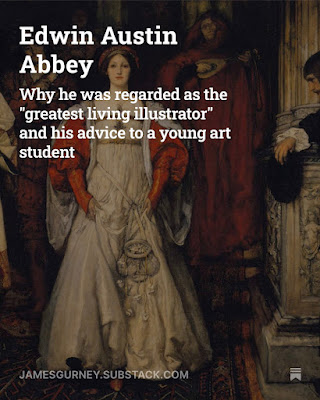

'You should be sketching always, always'

Abbey wrote to an art student: "You should be sketching always, always. Draw anything. Draw the dishes on the table while you are waiting for your breakfast. Draw the people in the station while you are waiting for your train. Look at everything. It is all part of your world. You are going to be one of a profession to which everything on this earth means something." More on Substack

Is the Computer a "Bicycle for the Mind?"

Steve Jobs wanted the personal computer to be like a “bicycle for the mind.” Has it worked out that way for you?

More on my Substack.

Eye Candy for Today: early paleo illustration by Henry De la Beche

Duria Antiquior by Henry De la Beche, watercolor. Link is to Wikimedia Commons page from which you can access a larger image.

Very often, scientists have had a secondary role as illustrators, enabling them to visualize the subjects of their investigations.

In this watercolor, early 19th century geologist Henry De la Beche paints his interpretations of fossils, then recently discovered by pioneering paleontologist Mary Anning in the region of Dorset in southwest England.

Though likely somewhat misinterpreted and odd looking by modern scientific standards, these creatures are surely no more bizarre then our more modern approximations of their appearance.

I don’t know the size or location of the original. When I ask Google for a translation of the title, it treats is as a person’s name. Antiquior by itself translates as “more ancient” so I assume that means “prehistoric” Perhaps Duria refers to Dorset; I don’t know.

Ferdinand Keller

When I first came across the work of German painter Fredinand Keller, who was active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I was immediately struck by the obvious influence of Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin.

Oddly, in what scant biographical information I can find on Keller, there is rarely mention of his overt admiration for Böcklin. The influence is not only glaring for me, but one of Kellers most commonly reproduced paintings is titled Böcklin’s Tomb (images above, top).

Though there are certainly stand out exceptions, the majority of Keller’s paintings that I can find on the internet share that brooding haunted feeling, almost to a surreal extent.

I particularly enjoy the textural qualities of stone in his paintings.